Innocent, Vol. 1

Innocent is tough to pin down. On the one hand, it’s a meticulously researched interval drama starring real-life figures akin to Charles-Henri Sanson, Casanova, Robert-François Damiens, and Jeanne Bécu, the type of factor you may see on Masterpiece Theater or HBO. On the opposite, it’s a lurid portrayal of a younger man’s corruption, crammed with over-the-top scenes of torture and debauchery that, deliberately or not, recall Justine, or The Misfortunes of Virtue. The tonal mismatch between its historic aspirations and its therapy of the principal character by no means gel right into a coherent story, nonetheless, leading to a good-looking however repellant mess that isn’t severe sufficient to maneuver the reader or ridiculous sufficient to be loved as camp.

The collection opens in 1793, then jumps again in time to disclose how Sanson advanced from a delicate younger man into the Royal Executioner of France. In making Sanson his protagonist, writer Shin’ichi Sakamoto has a significant hurdle to beat: Sanson executed virtually 3,000 individuals and championed the guillotine as a extra environment friendly, humane software for dispatching convicts. To make sure the reader’s sympathy lies firmly with Charles-Henri, due to this fact, Sakamoto commingles truth and fiction, depicting Sanson as a ravishing, raven-haired teen with flowing locks and trembling lips, the epitome of a guileless younger man. Everything makes Charles-Henri’s huge eyes glisten with tears: the merciless feedback of boarding faculty classmates, the sound of a flute, the sight of a ravishing younger aristocrat. He’s additionally liable to outbursts of teenage indignation and matches of nausea, unable to abdomen his father’s classes on how you can decapitate an individual with a single blow.

For all of the feverish dialogue and graphic violence, there’s virtually no significant character growth, as Sakamoto appears extra intent on demonstrating Charles-Henri’s capability for struggling than in depicting a flesh-and-blood particular person’s efforts to withstand his future. In one of the vital egregious examples of this tendency, Père Sanson tortures his son with strategies cribbed from the Book of Martyrs: he shackles Charles-Henri to a chair, deprives him of meals and water, pierces his pores and skin, and pulverizes his legs with a sledgehammer in an effort to bend Charles-Henri to his will. The true horror of the scene, nonetheless, is undercut by the way in which during which Sakamoto luxuriates in Charles-Henri’s wounded physique with similar fervid zeal as Titian painted the Crucifixion; Charles-Henri is stripped to waist and strapped to a pole, his palms tied above his head as he cries out in bewilderment. And if these Baroque thrives aren’t sufficient to wreck the scene’s emotional authenticity, the cartoonishly evil Père Sanson is; he’s much less a fully-realized character than a foil for Charles-Henri’s innocence, susceptible to creating over-the-top pronouncements that might be proper at residence in a Nicholas Cage flick.

If the narrative disappoints, the paintings doesn’t. Sakamoto attracts luxurious costumes and grand estates, lavishing appreciable consideration on small however traditionally significant particulars—a china sample, the buckle of a shoe—in a meticulous effort to evoke the fabric tradition of eighteenth century France. His actual reward, although, is making obscure historic figures come to life on the web page. Anne-Marthe Sanson, the matriarch of the Sanson clan, is a first-rate instance: she seems to be like a chook of prey with a piercing stare and sharp nostril, an impression bolstered by the way in which her fichu drapes throughout her chest like a ruff. In a number of key scenes, Sakamoto illuminates her from under, casting her face into shadowy aid to disclose the total extent of her hawkish vigilance:

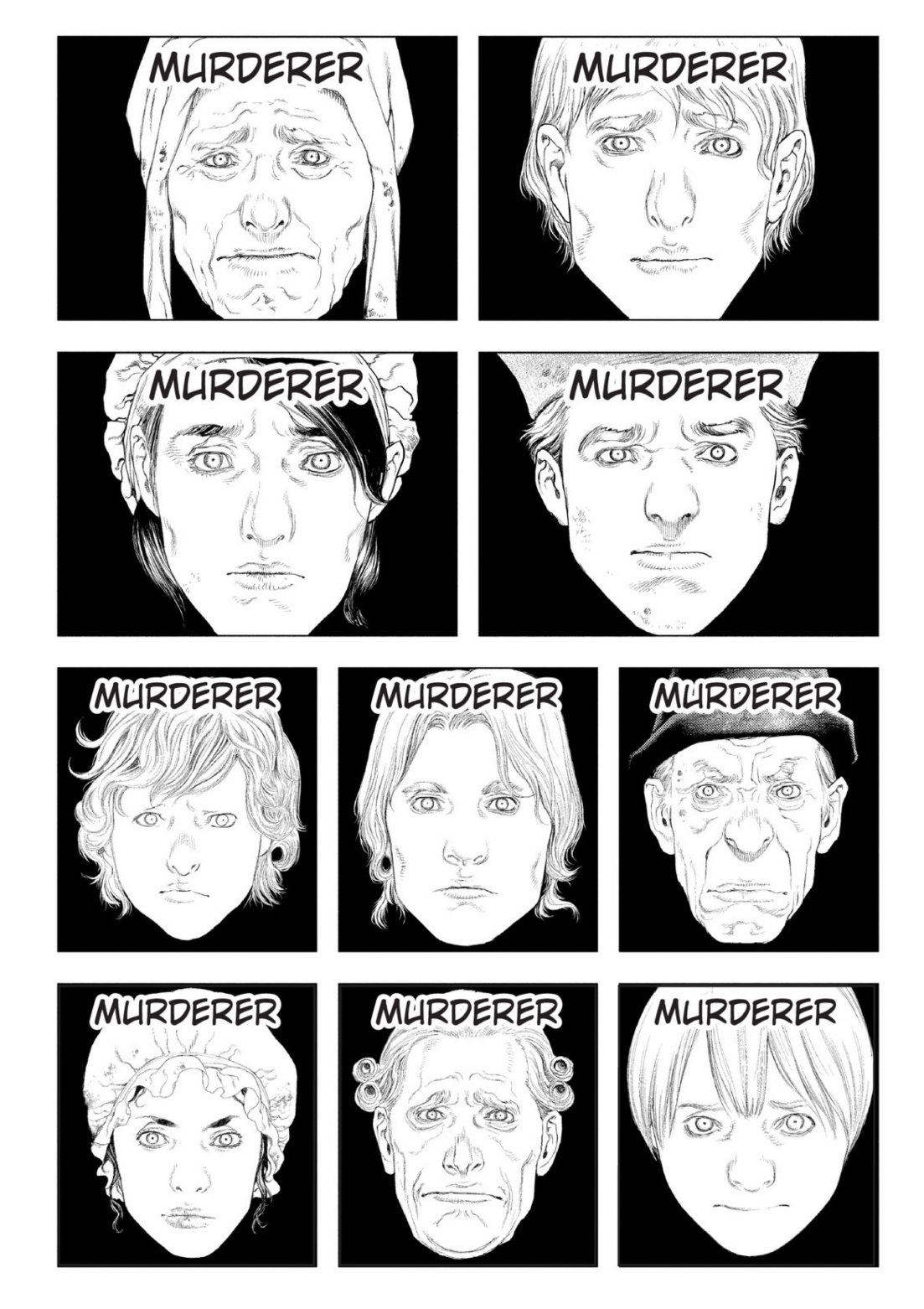

Sakamoto additionally has a aptitude for utilizing abstraction, fantasy, and non-sequiturs to disclose his characters’ innermost ideas. Not all of those gambits work; in a single visually jarring second, for instance, Sakamoto depicts Charles-Henri in trendy streetwear, a picture that serves no apparent dramatic goal. Other scenes, nonetheless, are devastatingly efficient in conveying the total extent of Charles-Henri’s paranoia and loneliness. After botching the execution of an acquaintance, Sanson seems to be out on the crowd and sees a motley assortment of faces observing him: Sakamoto then repeats this motif, including an increasing number of faces:(*1*)It’s a easy however highly effective sequence: we really feel the collective weight of the gang’s revulsion and the person opprobrium of everybody who witnessed Sanson’s orgiastic show of violence. At the identical time, nonetheless, we really feel Sanson’s rising sense of terror and confinement, imprisoned in a task he loathes and unable to flee the scrutiny of commoners and noblemen alike.

Sakamoto then repeats this motif, including an increasing number of faces:(*1*)It’s a easy however highly effective sequence: we really feel the collective weight of the gang’s revulsion and the person opprobrium of everybody who witnessed Sanson’s orgiastic show of violence. At the identical time, nonetheless, we really feel Sanson’s rising sense of terror and confinement, imprisoned in a task he loathes and unable to flee the scrutiny of commoners and noblemen alike.

These form of emotionally resonant scenes are few and much between, nonetheless, as Sakamoto is extra all in favour of exhibiting Charles-Henri’s martyrdom than making him into an actual particular person; you’d be forgiven for pondering that Sanson was a real-life saint and never somebody who’s remembered in the present day for his enthusiastic embrace of the guillotine. Not really useful.

INNOCENT, VOL. 1 • STORY AND ART BY SHIN’ICHI SAKAMOTO • TRANSLATED BY MICHAEL GOMBOS • LETTERING AND RETOUCH BY SUSIE LEE AND STUDIO CUTIE • DARK HORSE • 632 pp. • RATED 18+ (Violence, nudity, language)